Read an Event

- De Soto Expedition / First Christian Marriage in the New World -1540

- The Monroe Mission - 1821

- The Chickasaw Council House and the Treaty of Pontotoc - 1832

- Thomas C. McMackin, "Father of Pontotoc", and the McMackin House - 1836

- Lochinvar - 1836

- Chickasaw Female College - 1851

- W.C. Falkner and the Railroad - (1825-1889)

- The Story of Pontotoc by E.T. Winston - 1931

- Natchez Trace - Prehistoric

- Bodock (Bois d' arc) Tree

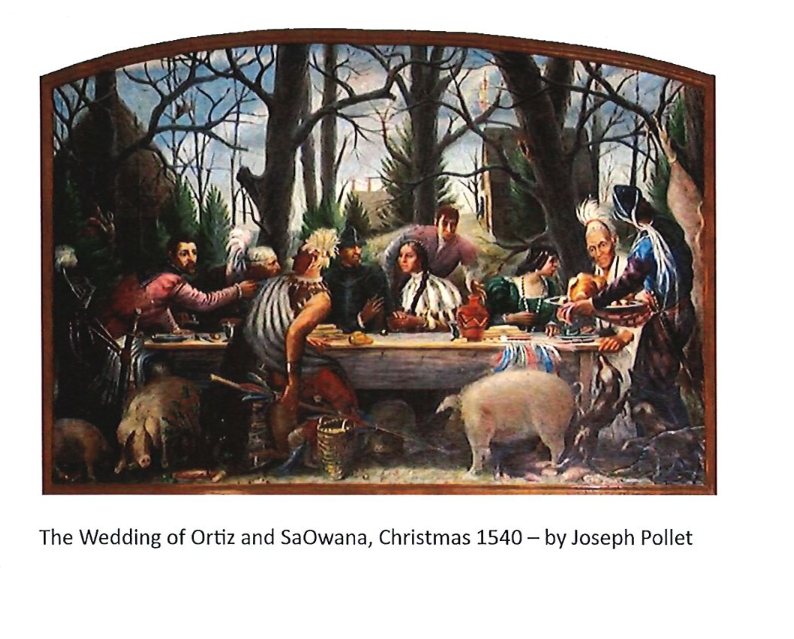

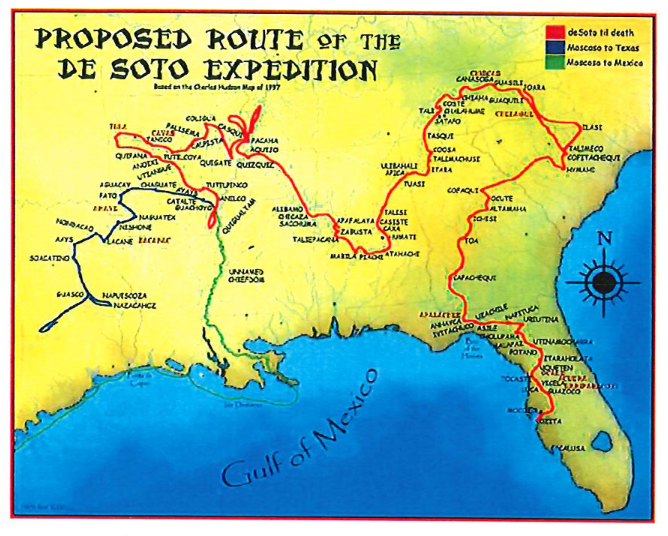

Spaniard explorer Hernando de Soto landed in what is now Florida in 1539 with six hundred men and traveled north and then west arriving in present day Mississippi in 1540. It is thought that he spent the winter near the Redland community in the southern part of Pontotoc County. De Soto’s party included Juan Ortiz, who had been captured by American Indians from a previous Spanish expedition nine years earlier. Ortiz escaped, joined De Soto, and began serving as a scout and interpreter for the expedition. Also with the group was SaOwana, daughter of a Seminole chief, who had been captured by the Spanish in Florida and was serving as a slave. Ortiz declared that he would marry SaOwana and free her from bondage. The historic event, thought to be the first Christian wedding in the New World, was held on Christmas day in 1540 in Pontotoc County. A Catholic priest performed the ceremony, and a feast featuring pork was a part of the celebration. The Spanish had brought pigs on the expedition as a source of food, and historians believe this was the animal’s initial introduction to North America. An important mural featuring this historic event hangs in the historic Town Square Post Office and Museum in downtown Pontotoc. The painting depicts the feast, including accompanying pigs, that followed the wedding. This mural was painted in 1939 by noted German born artist Joseph Pollet as part of the New Deal programs of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Museum is located at 59 South Main Street and admission is free and open to the public.

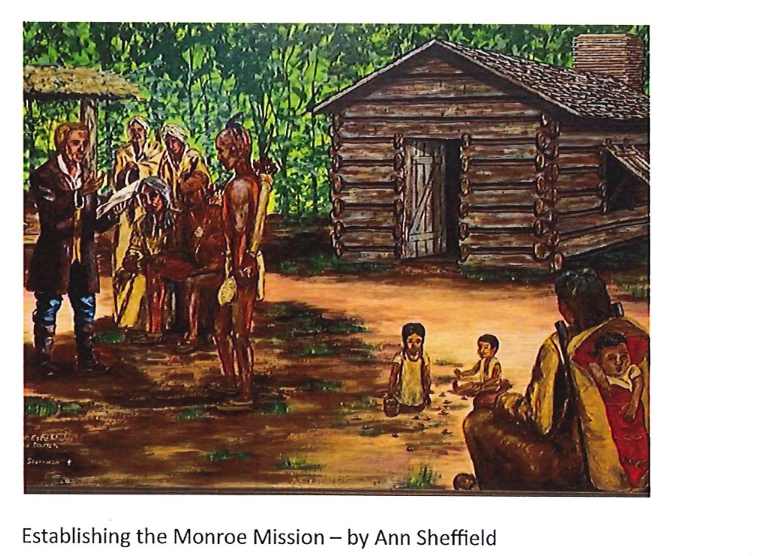

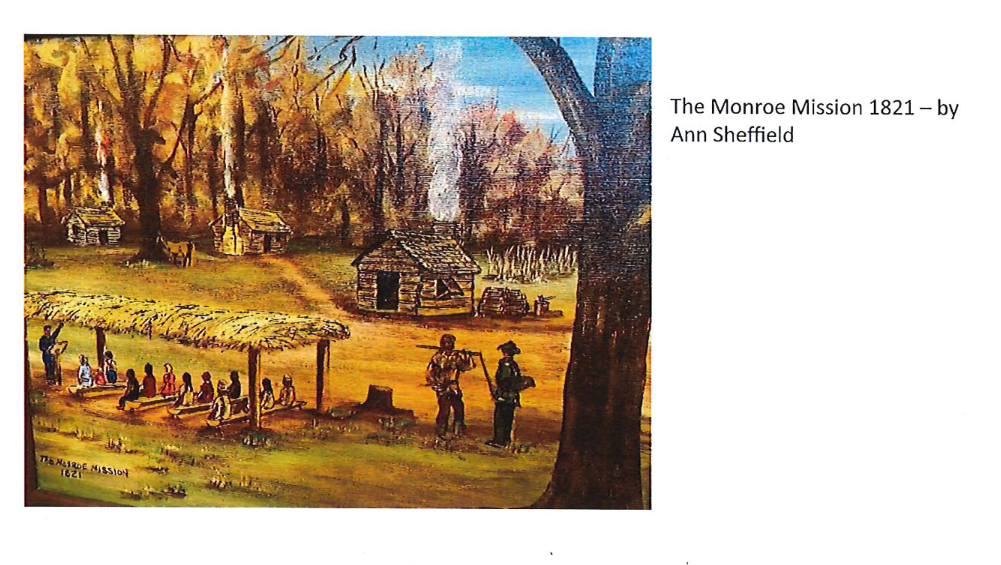

In 1819 Presbyterian leaders in the eastern United States resolved to establish a mission among the Indians in what is now Mississippi. Father Thomas C. Stuart was selected to establish this mission, and he arrived in Mississippi in May of 1820. The Chickasaw Council met on June 22, 1820, and granted him permission to stay and establish his mission. In January of 1821, Father Stuart brought several families from South Carolina to a location about six miles south of present day Pontotoc. This area was thought to be the most populous of the Chickasaw Nation with approximately 800 people living within ten miles of the mission. The settlement was named The Monroe Mission after the then president of the United States, James Monroe, and the families built houses, developed self-sustaining farms, and preached to the Chickasaws. Father Stuart soon started a school with sixteen Chickasaws attending, and this school grew rapidly. The mission’s first church, a 16 X 16-foot log cabin, opened in 1823. This structure was too hot for services in the summer, so the settlers built a large open air arbor nearby. One particularly interesting note about the church services – attendees included the white settlers, Chickasaw Indians, black slaves, and free blacks, truly a diverse congregation. The Chickasaw people were aware that having their children educated according to the missionary standards would benefit the Chickasaw people in adapting to the changing world. The numbers of Chickasaw children sent to the school soon exceeded the capacity and a new school was built two miles north of the Monroe Mission. The changes that occurred as a result of the breaking up of the Chickasaw Nation was difficult for the Mission, and it was abandoned as unsustainable in 1835.

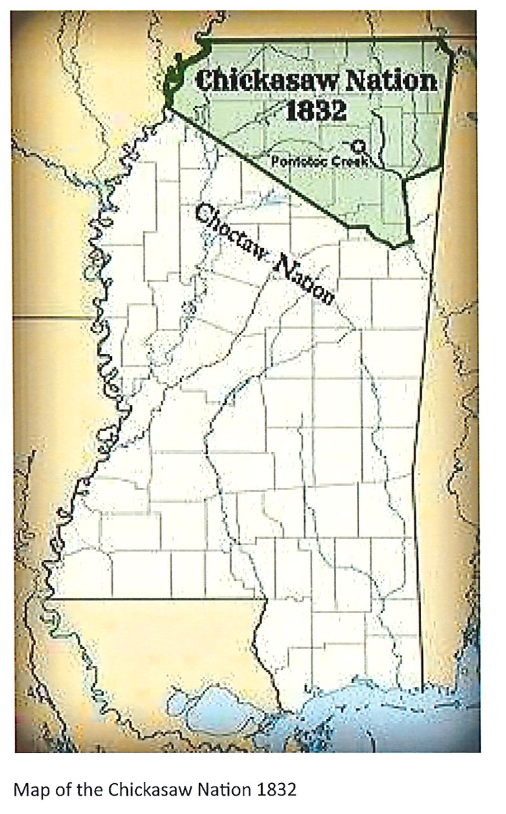

The Chickasaw Council House was built on the Natchez Trace at the village of “Pontatock”, which, in the 1820’s, became the capital of the mighty Chickasaw Nation. Chickasaw chiefs and other leaders traveled to Pontotoc each year to establish tribal laws and policies and to sign treaties. Each summer two to three thousand Indians camped nearby for this purpose and to receive the annual payments for lands they had sold to the United States government. The Treaty of Pontotoc Creek was signed at the Chickasaw Council House on October 20, 1832. John Coffee represented the US government, and the Chickasaws were represented by Ishtehotopa, Tishominko, Levi and George Colbert, and others. With this treaty, the Chickasaws relinquished more than six million acres of land to the United States in exchange for an equal amount of land west of the Mississippi River. Each adult Chickasaw was temporarily allocated land on which to live, improve, and eventually sell prior to their relocation to the west. Much of the proceeds of Chickasaw land sales were used to pay for the forced migration to the west and to purchase land from the Choctaws who had already been relocated to Oklahoma. The migration west of the final 4,914 Chickasaws and their 1,156 slaves took place in 1837-38 and was known as “The Chickasaw Trail of Tears”. While this migration was very difficult and damaged tribal culture and structure, it was the least traumatic of the migrations of the Five Civilized Tribes. The Chickasaws’ negotiation of the sale of their lands provided them with funding they were able to use to lessen the hardships suffered by other tribes being relocated.

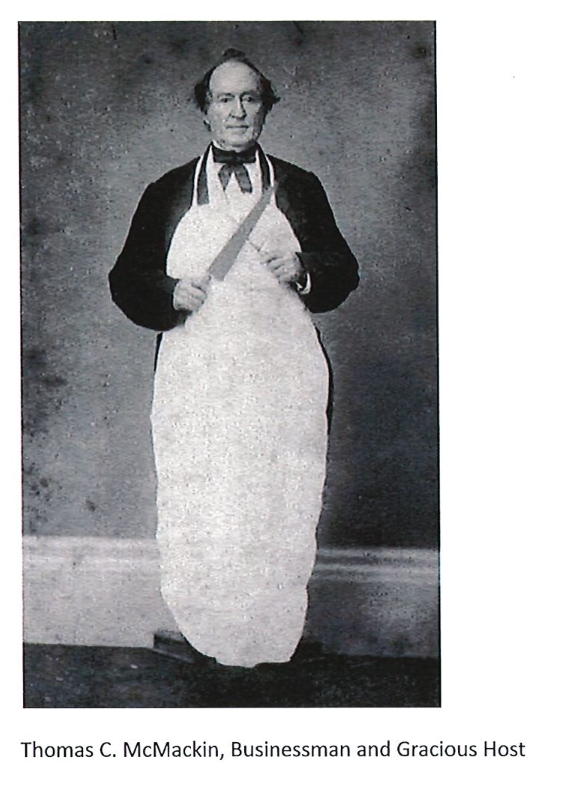

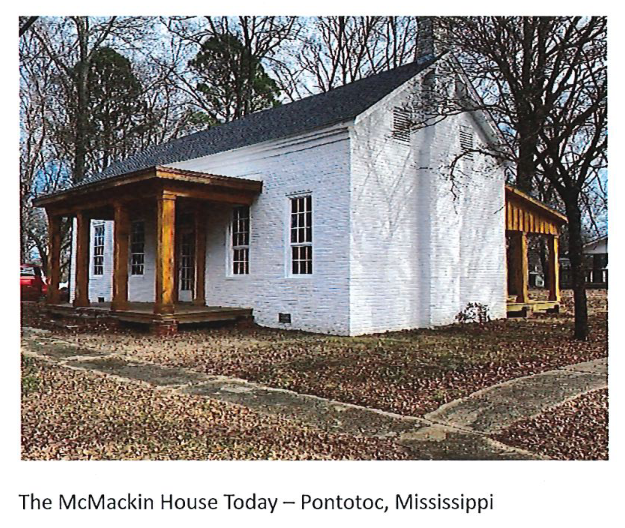

The Treaty of Pontotoc Creek, signed in 1832 by representatives of the US Government and the Chickasaws, laid the groundwork for the eventual migration of the Chickasaws to Oklahoma. This migration opened 6,000,000 acres to thousands of settlers and land speculators who came to this area looking to make their fortune. Thomas McMackin, widely recognized as possessing extraordinary business savvy and the heart of a gracious and generous host, came to Pontotoc to meet the needs of the hoards of travelers arriving daily. McMackin organized wagon trains loaded with all manner of food and supplies urgently needed by the land speculators who camped in the area for months while waiting for government agents to complete land surveys and distribution plans. McMackin once served 1,100 persons at one time in the open air with “an abundance of delicacies, and a plentiful supply of champagne,” unheard of in the wilderness of North Mississippi. He was widely known to be exceedingly fair and a delightful host. His fine qualities and business sense served him well as he was able to obtain ownership of the prime location now know as Pontotoc. He donated land for the streets of the new town and had them surveyed and cleared. He also donated land for the new courthouse square and additional land “to be used for female education,” property that was developed into the Chickasaw Female College. Late in 1836 McMackin built a masonry house just south of the courthouse, and that structure still stands. The Pontotoc County Historical Society is currently working to save the house and develop it into a museum presenting the earliest history of Pontotoc as a town. The house is available for tours by prearrangement with the Society.

Robert Gordon, the youngest son of a noble Scottish family, emigrated to the United States in about 1810 at the age of 22, first settling in Cotton Gin Port on the Tombigbee River. He was a successful businessman and established a general store primarily to trade with early settlers to the area and Chickasaw Indians. His success led to him founding the city of Aberdeen which he named after his home in Scotland. Gordon married Mary Elizabeth Walton from a leading Cotton Gin Port family, and they had a son, James, who later served in the Confederate Army under Jeb Stuart and Nathan Bedford Forrest.

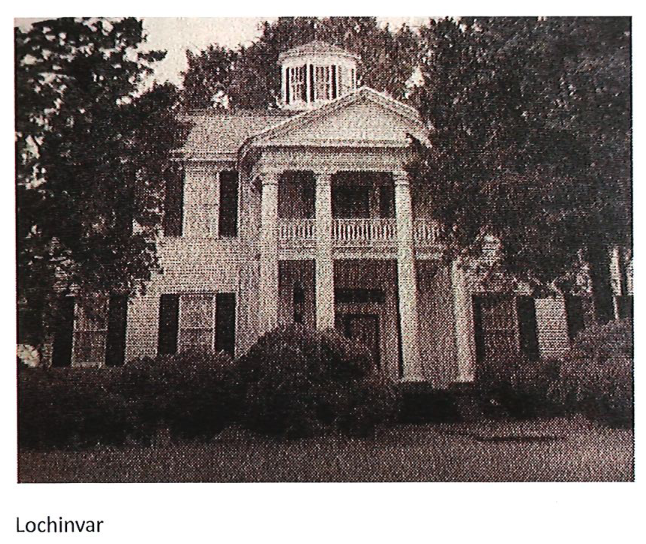

Gordon came to Pontotoc in 1835 to participate in the sale of Chickasaw lands which resulted from the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek. He successfully purchased 640 acres that had been allocated to Molly Gunn, daughter of William Colbert. As Gordon prospered, he expanded his land holdings and is said to have eventually owned 300,000 acres in North Mississippi. Gordon built Lochinvar south of town in 1836, and it has been described as the grandest antebellum home ever built in Pontotoc County. Timbers were cut on the property from old forest pine, and the bricks were handmade on the property. Gordon brought master craftsmen from Scotland to oversee the construction, and the four columns were taken from a castle in Scotland, shipped to Mobile, and brought to Pontotoc by ox pulled wagons. Lochinvar remained in the Gordon family until 1900, when J. D. Fontaine, an attorney, purchased it. Dr. Forrest Tutor purchased the home from Fontaine’s son in 1966 and restored it. The house is on the National Register of Historic Places. Heavily damaged by a tornado in 2001, Lochinvar has once again been restored by the Tutors to its former glory.

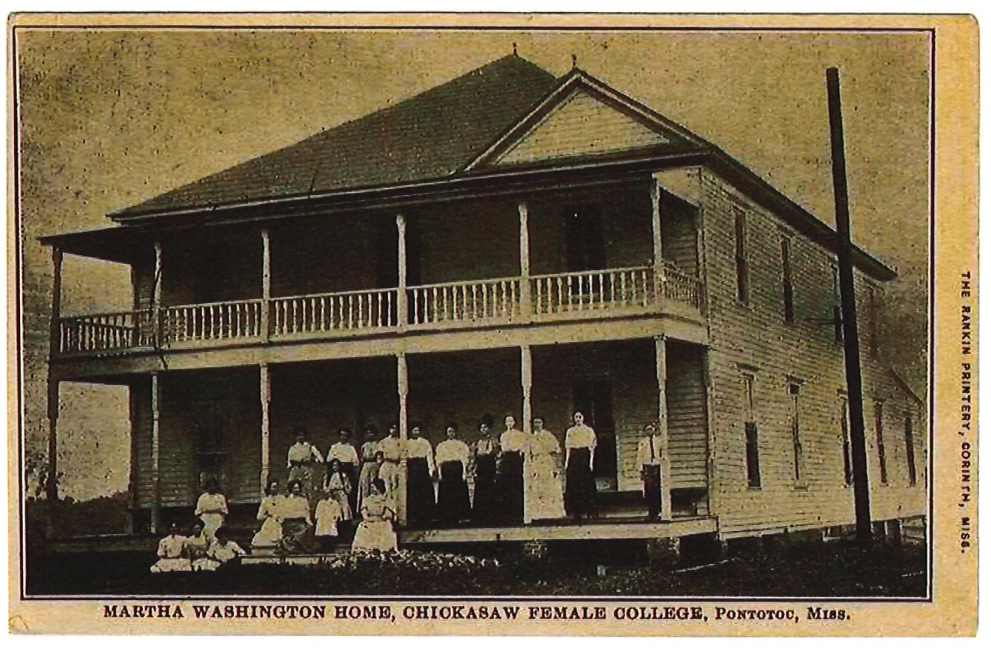

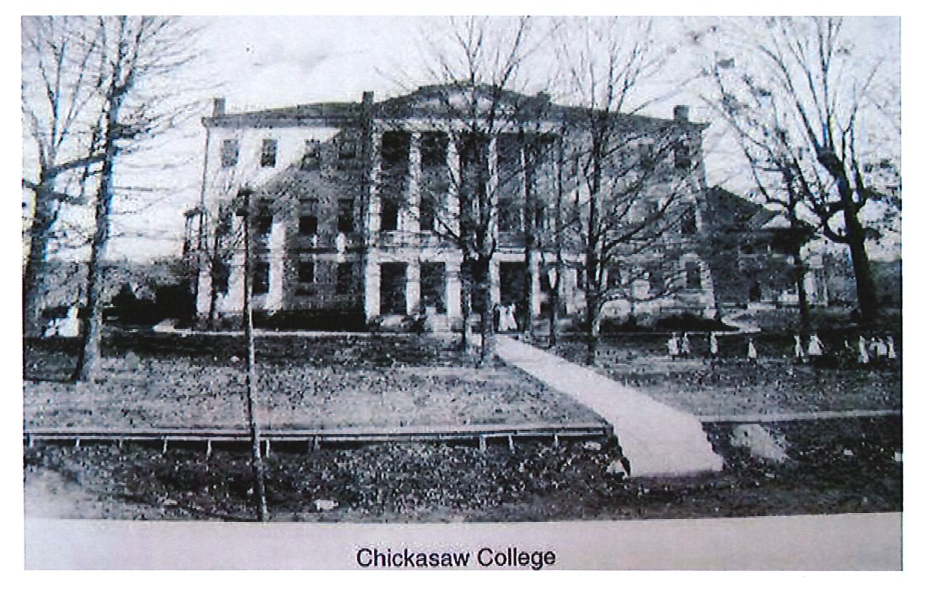

In 1836 Thomas McMackin purchased Chickasaw land and helped to found the town of Pontotoc. As part of his purchase agreement, he donated land for streets and a courthouse square, but also additional land to be used for female education, a most interesting stipulation for the mid 1800’s. The first building of Pontotoc Female College was completed on this land in 1838, and it was the first college founded for the education of girls exclusively in the State of Mississippi. The school was established for the purpose of “educating young ladies to be accomplished wives, mothers, and teachers.” In 1851 the financial burden of operating the college had become too great for the town, and an agreement was negotiated with~ the Presbytery of Chickasaw which took over the college and renamed it the Chickasaw Female College. The college offered courses in arithmetic, geography, English, grammar, history, philosophy, chemistry, meteorology, geology, astrology, French, Latin, and Greek. According to a report from the State of Mississippi Registrar’s Association in 1854, the Chickasaw Female College was on par with the finest female colleges in the South. Following examinations in 1860, Mr. A. H. Conkey, first president of the college, hosted a grand celebration as the specter of war hung over the land. Dragoons and infantry training in the area attended the party, but the College was soon to undergo significant changes. During the Civil War, classes were suspended, and the Institute Building of the college was used as a hospital for a short time by both the Union and Confederate armies. Mr. Palmer, the school’s math teacher, volunteered to fight for the Confederacy and was killed at the first Battle of Manassas. The College reopened in 1867 and succeeded for many years by adapting to changing times. The school expanded the age group of students being trained and began accepting male students as well. Despite these changes and assistance from wealthy benefactors, the college closed in 1936 after many years of financial struggles. The site on South Main Street is now home to the North Mississippi Medical Center – Pontotoc, long known as the Pontotoc Hospital.

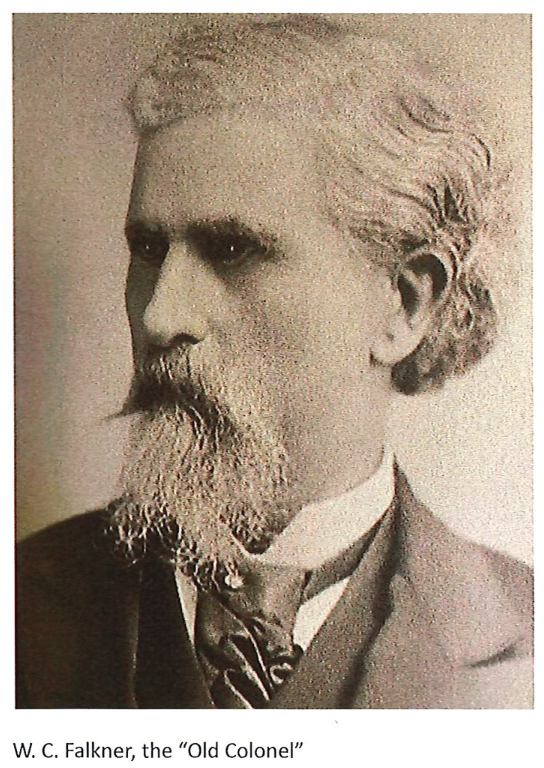

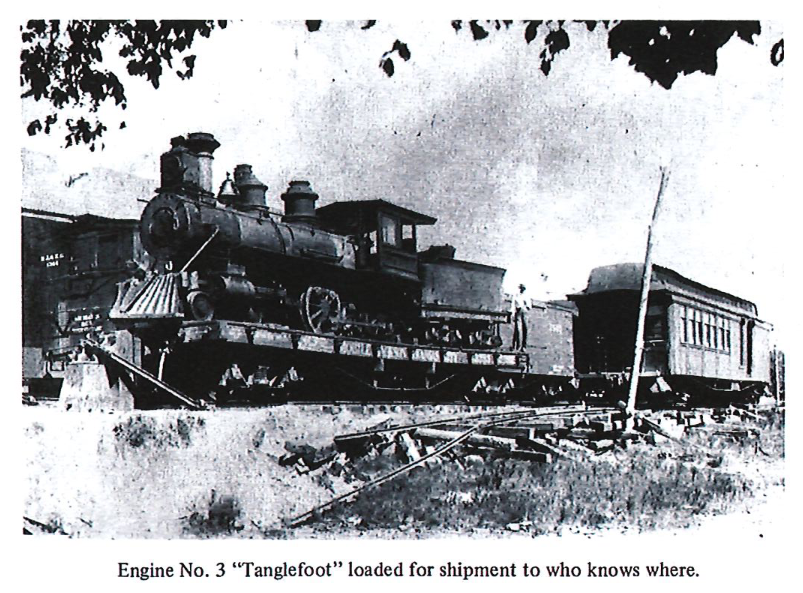

William C. Falkner, also known as the Old Colonel, was a soldier, lawyer, politician, businessman, and best-selling author, and he was successful in most of what he attempted. He fought in the Mexican American war and in the Civil War rising to the rank of colonel in the Confederate Army. Colonel Falkner

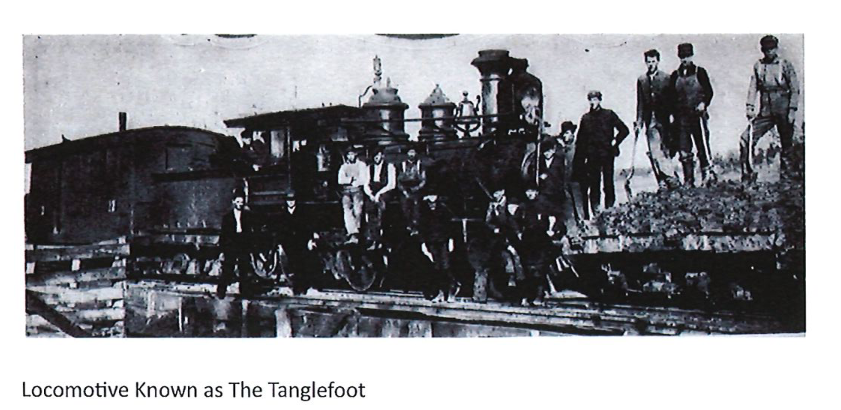

primarily lived in Ripley but had many associations with Pontotoc, most notable of which was bringing the first railroad to this town in 1888. On July 4th of that year a huge celebration was held to mark the arrival of the first locomotive to Pontotoc, an event that had a significant impact on the town. Crowds were estimated to be as high as 10,000 as people came from all over the northern part of the State to witness the event. Sheep, goats, hogs, and cows were barbecued overnight, bands played, games were held, and eloquent speeches were made, including one by Colonel Falkner presented “in his usual eloquent manner.” This celebration may have been the largest crowd to ever gather in Pontotoc. The Tanglefoot was the name of one of the first locomotives operated by Colonel Falkner’s railroad, and it made many trips to Pontotoc. Workmen turned it around overnight on the turntable located at the depot near Coffee Street in order for it to be ready for the next day’s trip. Colonel Falkner was tragically shot to death by his former partner on the town square in Ripley in 1889. In 2013, the 43.6-mile Tanglefoot Trail was built on the old railroad bed and opened as a multi-use trail for walkers, bikers, and runners. The Trail connects six communities along this historic stretch from New Albany to Houston with Pontotoc in the middle.

The Story of Pontotoc is a comprehensive history of Pontotoc written by local historian and newspaper editor E.T. Winston. The book was published by the Pontotoc Progress Print. Major sections include The Chickasaws, The Pioneers, and War and Reconstruction. In the author’s own words, the story includes “romances, legends, etc. which obviously do not belong to history,” but certainly these do add to the rich story of Pontotoc. The section on the war includes listings of soldiers with their units and place and time of their mustering into the Confederate army. Letters home to Pontotoc from far away fields are also included and enrich the story of the war and the local people. While The Story of Pontotoc is not a straight history, it is a very valuable collection of stories of the people and their lives lived in this area. Much of the material collected in this book would have been lost had Winston not collected and published it.

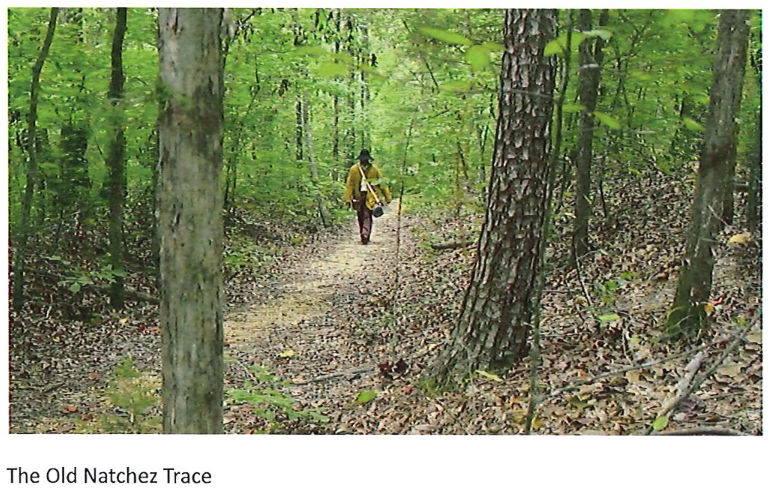

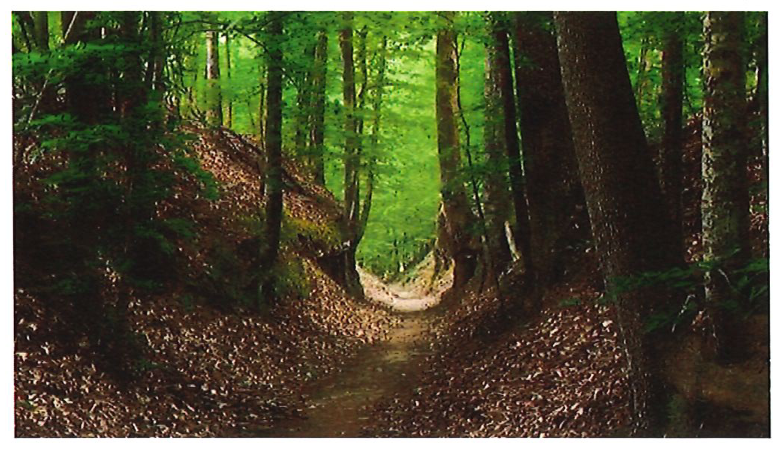

The Natchez Trace is thought to have originated from an ancient animal migration trail. Bison are often cited as likely to be the primary trailblazer for the Trace as they traveled in a northeasterly direction across the Southeast. It was used as a travel corridor for many centuries by American Indians, “Kaintucks,” European settlers, slave traders, soldiers, and future presidents. (Kaintucks were boatmen who transported merchandise down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to Natchez and then walked backed using the Natchez Trace. More than 10,000 Kaintucks walked the Old Trace in 1810 alone.)

Chickasaw Indians settled in northern Mississippi, western Tennessee, northwestern Alabama, and southwestern Kentucky and utilized the Natchez Trace heavily. They built their homes near the Trace using poles sunk into the ground which supported mud and reed daub walls with thatched roofs. In the late 1700’s ornithologist Alexander Wilson described the land cared for by the Chickasaws as “park-like” in appearance, a result of their diligence in nurturing their land. Along what is now the Natchez Trace Parkway, the Chickasaw people lived in the northernmost region, the Choctaw were in the central area, and the Natchez were the southernmost of these three tribes. Today, the Chickasaw Nation continues to be strong and resolute in preserving its historical connection with North Mississippi and the Natchez Trace Parkway, a 444-mile recreational road and scenic drive through three states.

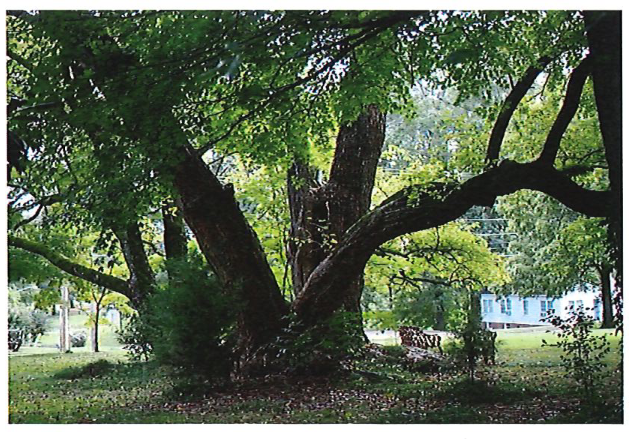

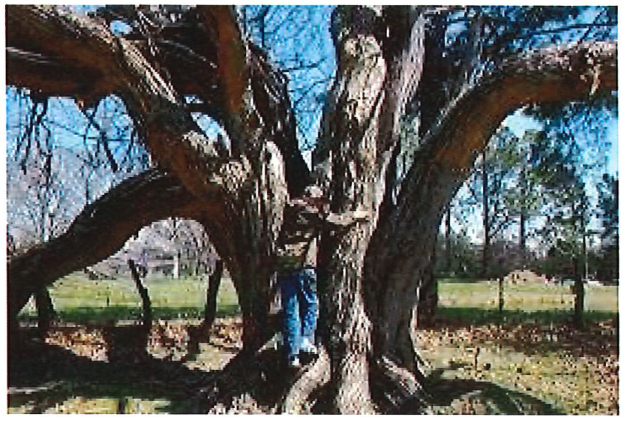

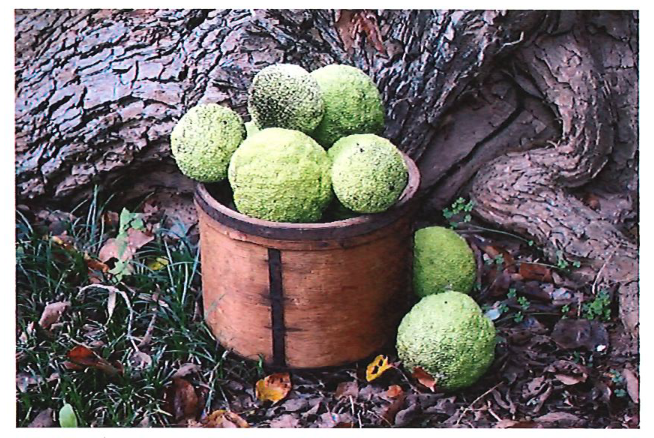

Bodock is a fruit bearing tree found in north Mississippi and most other states east of the Mississippi River and from the Great Plains almost to the Rocky Mountains, as well as parts of the Pacific Northwest. French explorers named the bodock tree bois d’arc, meaning “wood of the bow,” a name that has been passed through the ages in anglicized form as both bodark, and bodock. According to The University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, the bodock tree is known by a number of common names with many representing specific usage: bowwood, fence shrub, hedge, hedge apple, hedge orange, horse-apple, mock orange, naranjo chino and postwood. Chickasaws found the wood of the bodock tree to be very useful because it is strong and resistant to insects and rot, making it ideal for bows, arrows, and other wooden weapons and tools. The heartwood of bois d’arc when boiled makes an orangey, golden dye that is color-fast, so anything dyed with it maintains the color. Its fruit has been used as a natural bug repellent. Various studies have found elemol, an extract of Osage orange, to repel several species of mosquitoes, cockroaches, crickets, and ticks. One study found elemol to be as effective a mosquito repellent as DEET. Though the bodock’s density made it hard to cut and work, settlers found its heartwood useful for wheel hubs and railroad ties. Before the invention of barbed wire, bodock trees were planted to create hedge rows or fences. Afterwards, the durable wood was used for fence posts. Its bark was used in tanning leather, and an extract from root bark was used to dye clothes and baskets. In modern times, festival organizers in Pontotoc, Mississippi, chose to name Pontotoc’s annual arts and crafts extravaganza The Bodock Festival, partly because of the abundance of bodock trees throughout Pontotoc and Pontotoc County and partly because the largest bodock tree in the state stood on the grounds of Lochinvar, an antebellum home near Pontotoc. The tree was destroyed by the 2001 tornado that almost obliterated historic Lochinvar.

De Soto Expedition/First Christian Marriage in the New World – 1540

Spaniard explorer Hernando de Soto landed in what is now Florida in 1539 with six hundred men and traveled north and then west arriving in present day Mississippi in 1540. It is thought that he spent the

winter near the Redland community in the southern part of Pontotoc County. De Soto’s party included Juan Ortiz, who had been captured by American Indians from a previous Spanish expedition nine years earlier. Ortiz escaped, joined De Soto, and began serving as a scout and interpreter for the expedition.

Also with the group was SaOwana, daughter of a Seminole chief, who had been captured by the Spanish in Florida and was serving as a slave. Ortiz declared that he would marry SaOwana and free her from

bondage. The historic event, thought to be the first Christian wedding in the New World, was held on Christmas day in 1540 in Pontotoc County. A Catholic priest performed the ceremony, and a feast

featuring pork was a part of the celebration. The Spanish had brought pigs on the expedition as a source of food, and historians believe this was the animal’s initial introduction to North America.

An important mural featuring this historic event hangs in the historic Town Square Post Office and Museum in downtown Pontotoc. The painting depicts the feast, including accompanying pigs, that followed the wedding. This mural was painted in 1939 by noted German born artist Joseph Pollet as part of the New Deal programs of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Museum is located at 59 South Main Street and admission is free and open to the public.